Sitting in a workshop in the middle of a technical college in Gloucestershire is a car, but not just any car. This particular vehicle has inspired students of all ages to get involved in engineering, and in the next 12-18 months could become the fastest land vehicle in the world. Yet less than a year ago it all looked like the car would end up as scrap.

Bloodhound LSR, as it is now known, has come on in leaps and bounds from its previous incarnation as Bloodhound SSC. Under the ownership of Ian Warhurst, former owner of Melett, a turbocharger manufacturer, there is renewed optimism in the project. It is this enthusiasm that has carried the project to its latest stage, where later this month the car and its team will fly to Hakassan Pan in South Africa for high-speed testing.

‘I’ve really enjoyed watching the team rise to the challenge over these past six months,’ says Warhurst. ‘Something that has been talked about and planned for so long is now really happening, and the team have taken it in their stride. Our fantastic new location in the centre of a technical college at UTC Berkeley has helped the project come alive – the project is now in new territory.’

Warhurst noted that it was very important to remember that the team in South Africa have also risen to the challenge. ‘After so much work and several false starts, the Northern Cape Provincial Government didn’t hesitate to re-engage and have worked quickly and efficiently to help us finalise agreements and then mobilise the local workforce. This, in return, has brought much-needed employment to the area to help us clear and prepare the track,’ He said.

Final checks

Bloodhound aims to break the current land speed record, set in 1997 by Thrust SSC. That was the first car to break the sound barrier and achieved an average speed of 763mph. Andy Green, an RAF fighter pilot, was at the helm then, and he will also be taking the wheel of Bloodhound in South Africa when it aims to first attain 800mph, then, if conditions allow at a later date, over 1,000mph.

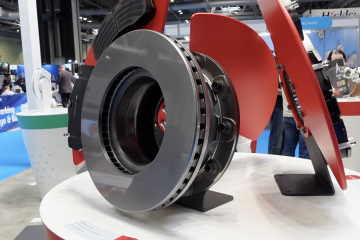

However, first, the team need to test. The runs planned at Hakassan Pan this year will see the car travel up to 500mph, allowing the team to check the systems, the aerodynamics, the solid aluminium wheels, and most importantly of all, the brakes.

‘The hardest thing about the land-speed record is not getting up to the measured mile, it is stopping after you leave the measured mile,’ explains engineering director Mark Chapman. ‘It is easier to put a bigger rocket in, a big jet engine in, and go that much faster. Slowing down before you run out of desert, only using stuff you are carrying on the car, is difficult.’

‘This year, therefore, is all about safety, how the car handles, how its stability is shaping up and very much how to slow the car down. Our primary way of stopping in South Africa will be a parachute system, with air brakes also deployed. One run will see us accelerate the car with the air brakes out, to gather data on their effectiveness,’ explained Chapman.

Fire up

Bloodhound’s new location in the middle of a technical college highlights how important the project is to develop an interest in engineering, a philosophy that it began with and has carried through despite troubled times. The team has visited schools and events to inspire young children through various activities, while older pupils have had an opportunity to see and learn about the car and the different systems used in its design and development.

Before departure, one of the final installation checks of the car’s state-of-the-art engine was to ‘dry crank’ it, checking all the systems are correct and working perfectly. This involves running through the start-up sequence and turning it over with no fuel or ignition.

A dry-crank test is a crucial stage of the pre-testing programme as it confirms the engine and all its ancillary systems, fuel and electrics are correctly installed and ready to fire up once the car is in the full-system test, confirming the engine can be started.

To perform the test the team used an Air Start Cart (a small jet engine) to blow high-pressure air into the onboard Aircraft Mounted Accessories Drive (AMAD) gearbox. This spun the jet’s turbine up to required speed and, once spinning, generated 3-phase AC power for the car, which then sent power to the jet engine’s fuel pumps. The test was successful, and in a few weeks, Bloodhound LSR will become one of the 10 fastest cars in the world, before its next journey to take the top spot.

Troubled times

While Bloodhound has been running for some time, the project had previously struggled for funding. In December, the previous company running it went into administration.

Reports suggest that Rolls Royce wanted the EJ200 jet engine, commonly found in the Eurofighter Typhoon, back as soon as possible. As there was no time to dismantle the car carefully, plans were drawn to cut it up, a move which would not have been reversible.

Thankfully, Warhurst was able to bring the company out of administration and has ploughed what he acknowledged was a ‘seven-figure sum’ into it. While Bloodhound LSR is still looking for sponsorship, it is a testament to the team that it was able to carry on at all, some working for free during the struggles. Today it looks more likely than ever that the car will make its date with destiny.